5 Takeaways from CalSTRS’ Private Equity Performance Report

In an era where private market investing is undergoing a sea change, CalSTRS' (California State Teachers Retirement System) latest private equity performance report provides a fascinating look at how one of America's largest pension funds navigates the complex landscape of alternative investments. With $352.5B in AUM (assets under management) and $67.5B deployed across different private equity strategies, CalSTRS' performance data provides rich insights for institutional investors that need to deploy large pools of capital.

In this post (and through a venture capital lens), I first explore the key objectives of a large institutional investor. Then, I highlight the key learnings from CalSTRS’ PE returns:

Traditional buyout strategies dominate private market investing

The long time horizon of private equity distributions

How IRR (internal rate of return) figures paint a “rosy picture” of private equity

How venture capital compares to its siblings, growth equity and traditional private equity

The collapse of investments into venture capital funds

I also provide commentary on how LPs (limited partners) can think about fund investing. As a bonus, I’ve open-sourced the code & data I used to run the analysis. Let’s dive in!

What are limited partners looking for?

To level set the conversation, I’ll first go over what limited partners are looking for as they allocate capital. For this post, I’ll focus on pension funds and endowments. These entities have billions, and sometimes up to hundreds of billions of dollars to deploy.

The objectives of a pension fund like CalSTRS are as follows:

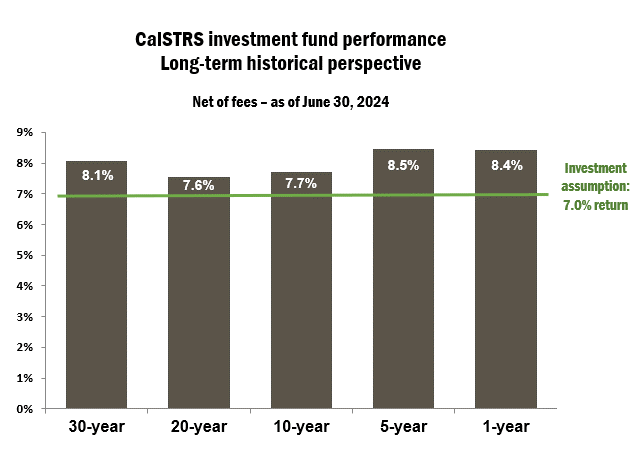

Maintain or grow its assets via contributions from payers (e.g. teachers who are still working) and investment income while meeting its pension payout obligations (and adjusting for inflation). In the chart below, we see that CalSTRS has been able to outperform its assumed 7% return

Ideally, a pension fund / endowment’s strategies are uncorrelated from each other to reduce volatility during difficult market conditions

An institutional LP might invest in private equity in hopes of generating superior returns relative to public equities (illiquidity premium). This is not the only strategy, as Nevada’s pension fund is predominately allocated to index funds

PE helps smooth out returns (e.g. the S&P 500 suffered a 50% drawdown during the Great Financial Crisis). Few investors during these periods can withstand the pressure to not sell. Illiquid assets like PE allow the overall portfolio to have less volatility (private market assets aren’t marked to market daily). This built-in illiquidity serves as a forcing function because investors can’t panic sell — and funds from these vintages tend to exhibit outperformance

With these objectives in mind — let’s see how CalSTRS’ private equity funds performed.

Traditional buyout strategies dominate private market investing

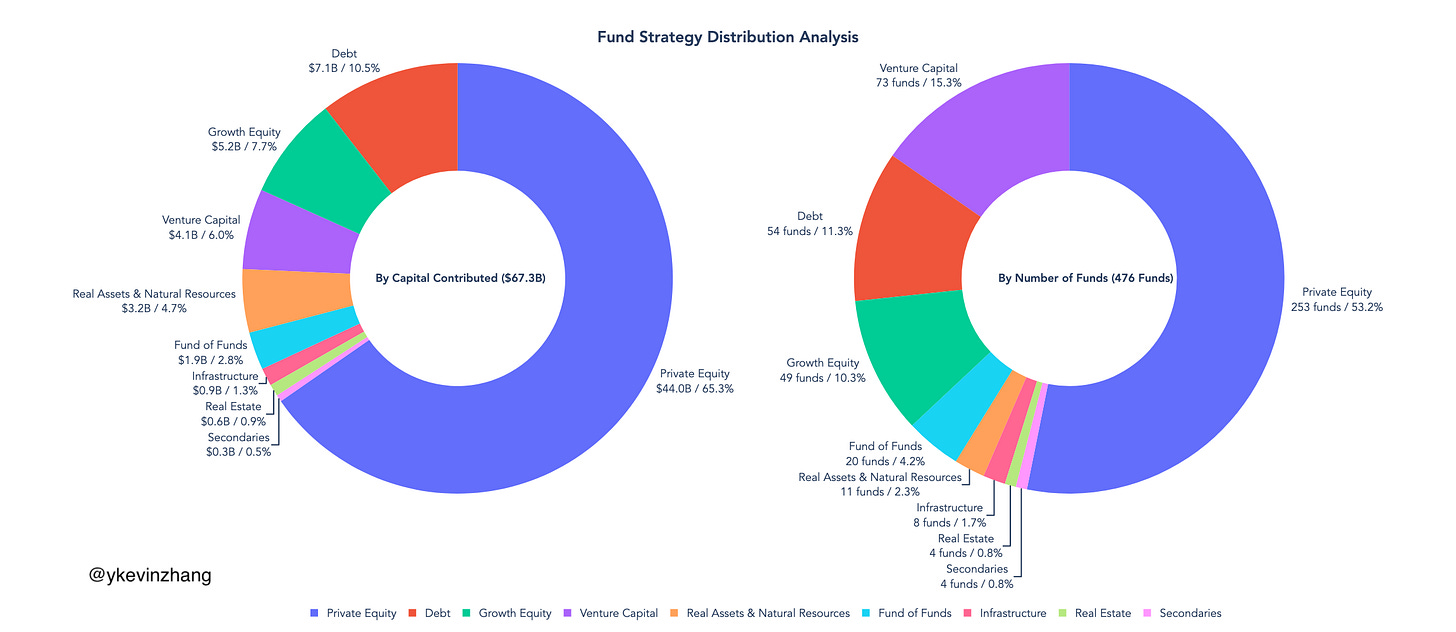

Starting from a 10,000 feet view, we see that most capital is deployed in “traditional” PE (e.g. buyout), both in terms of dollars allocated and number of funds. At this scale, the mental model to have is that an institutional investor wants a specific strategy in aggregate to generate a certain level of return. What this means is that if CalSTRS allocates $50M in one fund, and that fund triples (net of carry), it only returns $150M to CalSTRS. This barely moves the needle when compared to an asset base of over $350B! What LPs want, therefore, is to be able to deploy capital at scale (e.g. generate some multiple of capital on tens of billions of dollars deployed). Traditional PE is well suited for this given its ability to absorb billions / tens of billions of dollars per fund. Now, with a VC lens, we see that venture capital is less than 10% of total capital deployed in CalSTRS’ $67B PE strategy (and just over 1% of its overall $350B asset base).

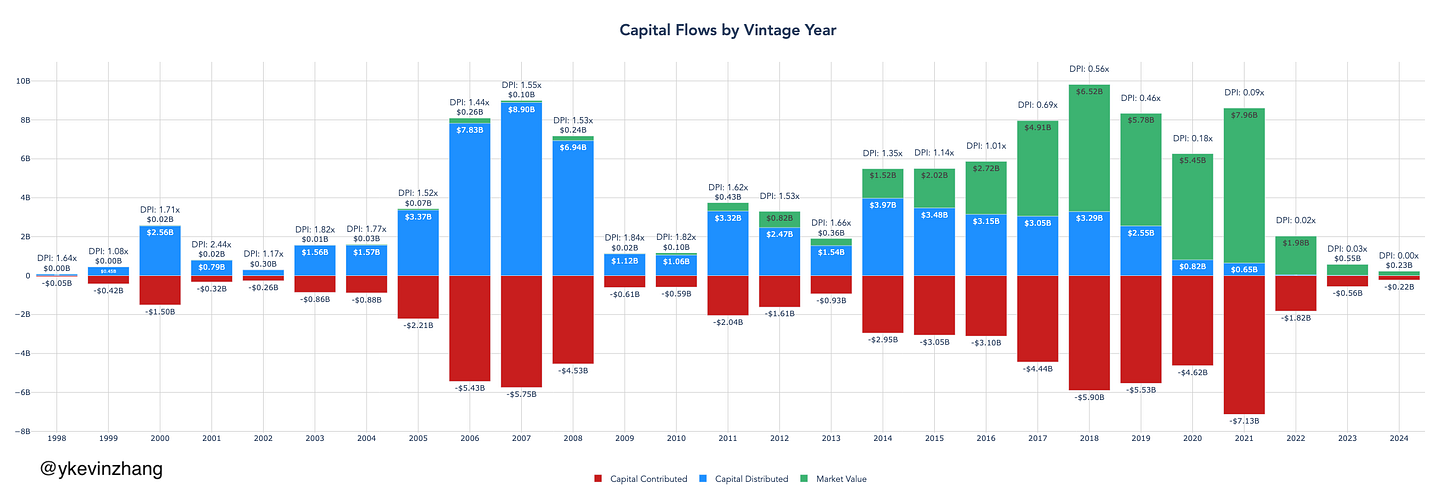

Going one level deeper into capital contributed by vintage year, we saw significant capital deployed leading into the Great Financial Crisis (GFC). Once we hit 2009, however, deployment fell off a cliff. Then, from 2014 onwards, there was a ramp up in deployment all the way through 2021 (peak ZIRP). Starting from 2022, as interest rates began to pick up and exit options disappeared (both for IPOs and significant M&As), the denominator effect kicked in (the collapse of public equity prices made most LPs “overweight” private equity), and capital deployed across all strategies drastically declined. One call out here is that the CalSTRS data is recent as of June 2024 so actual capital contributed in 2024 should be higher.

Distributions take more than a decade to fully realize

Next, let’s look at returns. One key metric that investors use is DPI (distributions to paid-in, defined as the ratio of dollars returned to an LP, relative to the dollars invested). This can be visualized by the graph below:

The red bar denotes that capital that is contributed for the given fund vintage (actual capital calls may not line up exactly with fund year)

The blue bar denotes capital that is returned to CalSTRS from a given vintage.

The green bars represent the market value of the investments that have not yet exited

I’ve also labeled the DPI. As an example, CalSTRS’ investments in 2007 returned ~$8.9B vs. ~$5.7B deployed, which gets us our ~1.55x DPI

If we look at 1998-2013 (the time period when most of the investment value has been realized), DPI ranges from a low of 1.2x to a high of 2.4x, in 2002 and 2001, respectively. When averaging the total dollars returned ($43.9B) vs. total dollars contributed ($28B), we have a 1.57x DPI.

From 2014 onwards, we see that there’s still quite a bit of “residual” value left ($1.5B of residual value vs. $2.9B allocated for the 2014 vintage). If we only look at the DPI from 2014-2024, we have $21B distributed vs. $39.3B contributed. This DPI is only 0.54x! If we add the green bars (giving us the TVPI, or total value to paid-in), we get 1.54x, which is similar to historical returns.

The worrying trend here is that companies are electing to stay private longer (Stripe, SpaceX, and Databricks were all founded over a decade ago), or cannot exit at the valuations they want. This results in lower IRR if late-stage companies are growing more slowly at exit, dragging down the returns earned from the earlier years of explosive growth. This dynamic, as well as LPs’ need for liquidity, has led to the increase of secondary / continuation funds. Now, if 2025 becomes a banner year for exits, more of the green bar would be turned into actual distributions.

Internal rate of return paints a more rosy picture

Turning our attention to IRR, we see that PE does sometimes yield outperformance vs. the S&P 500, which generated annualized return of 10.13% since 1957 (as of December 26 2024). Here, CalSTRS’ private market investments outperformed the S&P in 18 of the 27 vintage years. This is accounting for investments post-2020 and the effects of the J-curve.

Now, it’s worth mentioning that IRR figures can be slightly misleading here:

Some vintages didn’t really compound much (low DPI relative to IRR)

2001 and 1998 are outlier years (e.g. 2001 had a 32.1% weighted IRR!). The reason here is the small number of funds in those vintages (1 fund in 1998 and 3 funds in 2001)

Funds may still be carrying marks that don’t reflect the true exit value of the underlying assets. For example, many VC investments were marked up in 2021, which, even after subsequent adjustments, would have inflated valuations

Figures before 2014 give us more “accurate” IRR (most of the investment value has been realized for those vintages). Here, PE outperformed 10 of 16 years (from 1998 through 2013)

Venture capital exhibits higher variance in returns

So how does VC compare to growth and traditional PE / growth equity? Looking at DPI figures below, we see a couple interesting data points:

There’s a “spike” in returns for funds from the Great Financial Crisis vintages, with VC, growth equity, and private equity all achieving 3x DPI in specific years. This intuitively makes sense: asset prices were depressed, and entrepreneurs who chose to build companies likely exhibited a level of resilience that some entrepreneurs in more “frothy” times did not

It takes a long time to generate even 1x DPI. Growth equity was the only strategy that generated more than 1x DPI in 2016, which is ~9 years ago. The last VC vintage that generated 1x DPI was in 2014, 10 years after capital was contributed!

One reason is that companies that missed the 2021 exit window had very little opportunity to exit, given acquisitions were muted under Lina Khan’s FTC and IPO markets were frozen

Turning our attention to IRR in the chart below, we have the following takeaways:

Private equity has the “smoothest” returns (especially after 2010), while growth equity provides somewhat more elevated returns

IRR was crushed in the past ~5 years. This means one of two things. We’re either seeing an extended J-curve or we’re undergoing a natural evolution of PE as returns get compressed

Venture capital has somewhat underperformed, given that a very small handful of companies (likely in the low dozens) drive the majority of returns in a given year, so fund selection is crucial

There are a couple of additional insights (figure below). 2001’s PE returns was a monster 35%! Investigating the data further, we see that CalSTRS only allocated capital to 2 funds, and CVC European Equity Partners III in particular returned ~2.8x, good for 40% IRR.

The other interesting data point is VC’s 1998 returns, which generated a weighted IRR of 30.6%, but that the DPI was only ~1.6x! There are three factors at play. One, CalSTRS only invested in a single VC fund in 1998. Two, capital is generally called when there is an investment to be made (helps juice IRR). Three, these investments were likely sold off relatively quickly after the initial investment, so there wasn’t as much compounding.

VC funding has collapsed in the past three years

Finally, let’s look at CalSTRS’ VC allocation over the years, both in terms of absolute dollars deployed, and as a percentage of capital deployed across various strategies. As we can see in the graph below, VC is a small fraction of total capital deployed.

The takeaways here are:

2021 was a banner year for VC, given record distributions as companies went public or were acquired. The proceeds from these exits were then recycled to new funds that year

Since then, capital contributed fell significantly below historicals, with only $2M contributed in 2024 (though this data is only covers the first 6 months of the year)

There is a delta between capital committed vs. contributed. For example, CalSTRS committed an aggregate of $30M to Spark Capital in 2024 (across Spark’s Fund VIII and Spark Capital Growth Fund V), but hadn’t contributed any dollars yet

How to think about investing in VC funds

As we can see from the analysis above, it’s incredibly difficult to deploy capital at scale while balancing various investment objectives (minimum return hurdle, reducing volatility, investing in non-correlated assets, etc.). At CalSTRS’ scale, investments across multiple funds within a given strategy would naturally yield the returns of the overall asset class (whether that asset class is PE, VC, or something else). More broadly, with a $350B+ asset base, returns theoretically should asymptotically approach that of the broader economy.

Going back to the PE vs. investing in a public equities index debate, we see that CalSTRS does generate outperformance over public indices more often than not. Now, if the public markets continue to outperform, and returns from PE strategies compress further due to competition for top deals, I expect the spread between public equities and private equity to further tighten.

So how should LPs allocate to different PE strategies? One framework is figuring out how much capital each “sub strategy” within an asset class (e.g. buyouts, VC) can absorb. I use VC as an example below.

Pre-seed/seed firms

At pre-seed/seed, the name of the game is maximizing shots on goal. The rationale is that this is the “cheapest” stage (unless you’re Bret Taylor and you get to raise $100M+ at a $1B valuation) because founders are often raising pre-traction and funds can get meaningful ownership. The trade-off is that because these startups have a much higher probability of failure, LPs need a much higher number of investments to hit that one outlier. According to Carta, only ~15% of Seed stage startups raised a Series A in Q1 2022, down from ~30% in Q1 2018! This means that it’s even more risky now to invest at this stage — so having enough coverage really matters!

The required number of shots on goal also necessitates more fund managers, as each manager can only invest/manage a certain number of investments. The optimization function therefore is to maximize variance (invest in a lot of good founders), as variance to the downside is merely losing your principle (1x of invested capital), but variance to the upside is YC buying 6% of Airbnb for $20,000. One recent dynamic is established partners leaving larger VC platforms to join / create their own pre-seed/seed firms, which makes the firm selection problem harder.

Because pre-seed/seed funds tend to be comparatively small, LPs like CalSTRS need to invest in a larger basket of funds to have a higher probability of strong returns. CalSTRS is doing that via its “CalSTRS New&Next Generation Manager Fund” set of funds (administered by Sapphire Partners). As an aside, I believe this segment of VC makes the most sense for smaller LPs, where fund outperformance can have a material impact on portfolio-level returns, whereas it wouldn’t really move the needle for extremely large LPs (where investing into emerging managers seems more like a relationship building exercise).

Series A firms

Series A’s are where the degree of variance reduces significantly, and where returns are concentrated to a very small number of funds (I would guess the bulk of returns is concentrated in the top 30-50 funds). This is due to the fact that at the Series A, companies tend to have actual financial traction (or achieved some other major milestone). As a result, Series A’s have also historically been the most competitive round (the derisking from seed to A often supersedes the additional cost firms are paying for).

Here, the optimization function is access into the best funds. The mental model is that if we assume there are 50 “top funds”, and each fund on average raises $500M for a 3 year deployment cycle, the entire Series A ecosystem would be something like $25B over 3 years, or ~$8B per year! That’s actually a very small figure when there are so many LPs in the world!

Asset Aggregators

Asset aggregators are massive multi-stage firms—at every stage, these firms would raise large funds relative to their stage-specific peers. We are seeing this trend play out in real-time, with nine US funds pulling in ~50% of all LP dollars in 2024. As a result, venture is becoming an asset aggregator vs. a specialist game, with firms in the middle getting squeezed out. The net result is that these asset aggregators have the AUM that rivals mid-sized PE shops.

This is a double-edged sword. On one hand, these funds have the firepower to back companies that require significant capital (like an OpenAI or Anduril, even at the growth stages) and generate massive returns, whereas other funds wouldn’t have the capital to even compete. On the other hand, these funds have enormous pressure to deploy capital, potentially resulting in returns that end up tracking the average returns of venture capital, which may not be what LPs signed up for! I predict a bimodal outcome for these funds — they either hit the next $100B+ outcome, or end up blowing up.

This type of fund is the most optimal for large LPs (assuming they can generate slightly premium returns relative to some benchmark), because it’s much “easier” to invest in a small number of name-brand, large funds vs. making bets on a large basket of early stage funds.

Key Takeaways

So what are the key lessons to draw from our analysis?

From a returns perspective, we will likely see a continued compression in returns and elongated time to liquidity given structural changes to private market investing

At the same time, PE strategies generated superior returns during periods like the Great Financial Crisis. So if institutional investors want to allocate to the private markets, they have to allocate across vintages so that some vintages can “yank” up overall returns

Large institutional investors like CalSTRS have hard jobs! The challenge lies not just in generating strong, non-correlated, risk-adjusted returns, but in doing so at sufficient scale to impact overall portfolio performance

Which brings us to our fund managers. From a VC perspective, we’re in the midst of an era of extreme flux. Large funds (e.g. asset aggregators) will continue to raise from LPs like CalSTRS and sovereign wealth funds and generate “acceptable” returns at scale. What’s more interesting for me is at the early stages, where we are seeing the rapid birth / death of emerging managers and the entrance of other players (e.g. professionalized family offices)

Code & data

The code & underlying data lives here.

Analysis Methodology

I assume all capital is contributed the year of the fund (the “VY” column)

I used ChatGPT to segment fund types (e.g. PE, VC, Growth Equity, Fund of Funds, Private Credit), then manually checked the ChatGPT labels against PitchBook

Some discretion was used for the “bucketing”. As an example, a special situations fund that contains both buyout and credit strategies would be labeled “private equity fund”.

In funds where the specific strategy was unknown, I would label it as “private equity”.

Weighted IRR is calculated as IRR for a specific fund multiplied by the capital contributed for that fund, divided by total capital contributed for a given year

Huge thanks to Will Lee, Homan Yuen, and Andrew Tan for the feedback on this article. If you want to chat about all things investing, ML/AI, and the looming threat of ASI, I’m around on LinkedIn and Twitter!