TikTok, Robots, and Opportunities in Consumerland!

What can Western startups learn from Chinese consumer companies?

(This is a spiritual successor to last month’s article, “Parallel Tracks — Observations from the Jade Empire,” where I explored China’s technological advances relative to those of the US and the West, with China surpassing the West in certain high-end, leading-edge domains.)

In this (more light-hearted) post, I highlight some of the innovations on the “low-end” part of China’s technology stack. First, I look at how China’s extensive super-app ecosystem, the widespread use of computer vision, and urban population density has enabled Chinese consumers to achieve a level of consumer convenience that we can only dream about. I argue that due to various structural factors, many of these categories of Chinese innovations will not make their way to the West.

Then, I examine two areas that Western startups can borrow from their Chinese counterparts as they build their own products. I use two examples here:

New modalities, in combination with new UX/UI, can give scrappy startups a weapon to compete with more established incumbents. I introduce the concept of user generated content inversion as one mechanism that companies like 小红书 (Little Red Book) use to differentiate themselves from the brutally competitive landscape in China

Chinese consumer robotics startups’ focus on building revenue-generating products is the better approach compared to the more “research-focused” approach that many Western robotics startups have taken

Finally, I argue that despite the current “VC winter” in consumer investing, there are very interesting opportunities for consumer startups. Here, I present novel UI/UX (especially as we adopt more generative AI), and a focus on immediately monetizable consumer robotics as two sources of alpha that could lead to the creation of the next generation of iconic consumer companies.

Let’s dive in.

The name of the game in China is consumer convenience

China is the land of super apps

The clearest case of this “convenience” is the consumer mobile app ecosystem. Chinese mobile app users can essentially manage their entire digital lives with ~5 apps vs. the more than a dozen we need in the US/Canada.

To understand how someone might use these apps in a typical day, let’s use a concrete example:

Groceries: I realize I haven’t been eating my fruits and order strawberries and bananas on Meituan/美团 app. Delivery is free

Public transit: I board the Subway in Shanghai, using a QR code on my Alipay app to pay

Dinner & drinks: I buy a set menu for a hip Spanish restaurant on Dianpin (大众点评), which is owned by Meituan (美团). Payment is seamless because Dianpin is tightly integrated with Alipay

Rideshare: I don’t feel like taking the subway home, and use either Amap (高德地图) or Didi to take a car home, costing me only $10 for a 30+ minute ride

Food delivery: I’m still feeling hungry at night, and order KFC on the Meituan (美团) app at 1am in the morning

Throughout my entire day, I didn’t need to take out my wallet a single time

The above example only does a mediocre job of describing how convenient and cheap everything is. The chart below lists several “utility-focused” apps in China, and hopefully does a better job of highlighting the fact that each Chinese super app aggregates the functionality of multiple apps in the West.

The net result here is that this small handful of utility apps dominates consumer eyeballs in China.

A couple of observations from this:

The UI for many Chinese apps very much feels like a Western app built in the mid 2010s. The outdated UI, along with general high-UI density & features can lead to a confusing experience for new users. Despite this “legacy” UI, some of these apps are video first. Western consumers are slowly getting used to these high-UI density apps (through apps like Temu), however

The “convenience” afforded to local Chinese users is largely absent for foreign visitors. To use something like Alipay, you’d first need to upload your passport to even attach your credit card (which wasn’t even possible before!). Transactions over ¥200 RMB incur a 3% fee, and some capabilities are “gated” to local users/users with Chinese phone numbers. My understanding is that there is pressure from the Chinese government to change this, so it might not be a problem for long

One reason for this “convenience” is that Chinese users are required to map their 身份证 (identity card) to these apps, so that users can directly then book a flight or hotel. In the West, security/identity/fraud is largely offloaded to our existing credit card/payment processor stack, whereas in China, this is offloaded to the 身份证 and an app’s existing security capabilities.

The “traditional” way we think about building products for consumers is to be extremely good at one feature/use case. In China, the sheer quantity of features within one super app becomes a quality in itself. This creates a type of virtuous feedback loop where more features lead to heavier usage.

There is a heavy overlap of features across these super apps (e.g. one can book hotels on Amap, Meituan, or Alipay)

Given this remarkable convenience afforded to Chinese users, it’s logical to question why something like this doesn’t exist in the US. This brings us to our first set of structural barriers:

In terms of payments, incumbents Visa and Mastercard (and to a lesser extent Amex/Discover) have a stranglehold on the market and are able to charge 1.5-3.5% processing fees. Given that payment processing isn’t the core revenue driver for Alipay (Alibaba) and WeChat Pay (Tencent), these companies only charge merchants ~0.5% per transaction

The Chinese app ecosystem is still dominated by the BAT triumvirate (Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent). These companies are known to acquire fast growing startups as they compete for market share. This would be difficult in the US given the current antitrust environment

Technology adoption timelines: In the West, web-based applications came first, then mobile apps. In China, many workflows/use cases started out mobile-native. The same is true of payments, where China made a direct shift from cash to app-based payments/transfers

“Ambient” Computer Vision

Another area where technology has reached ubiquity is the use of computer vision. Here, the widespread use of facial recognition means that citizens can board trains without needing a physical paper ticket (or add an e-ticket on their Apple Wallet), go through sections of airport security, and easily enter/exit their local 小区/gated communities.

One reason these capabilities exist in China is due to the mandatory identity to app mapping. To use apps like Alipay, Chinese citizens must upload their identity card/身份证 information. For companies like Alibaba/Tencent, this is very much the cost of doing business in China. Once this mapping exists, users can get facial authentication for “free”. The other notable thing here is that both companies and governments will have much richer vision datasets vs. Western companies for future AI training purposes, given this lax privacy posture.

While other parts of the world (including the West) have also adopted some of this “ambient” convenience, it’s difficult to imagine the New York Subway system adopted something like this. Or, people willingly mapping their passports to, say, an app made by Facebook. Here lies our second structural limitation.

Population density, logistics, and cheap manufacturing

The final example of this technology-enabled convenience is enabled by the trifecta of the sheer population density of major cities in China, cheap human labor, and robust manufacturing capacity. The unit economics, for both the customers and the companies providing these services, make more sense in China vs. the US. Everything from bike/ride sharing to delivery services is significantly cheaper and gets higher utilization because of this population density.

One example is delivery in 美团 (Meituan), where the app guarantees that deliveries will be completed within a certain time. Imagine Doordash penalizing Dashers for late deliveries! The “reverse logistics” capabilities in China are equally impressive. A shopper might order 10 pieces of clothing to try on, but only keep one or two. That shopper might then schedule a next-day return, and a courier will do a home pickup for only ~¥8 (~$1 USD)!

The US, in contrast, has much lower population density (in fact, population density falls off a cliff after New York City). Unless we can drastically reduce the cost of logistics via automation, the US will always have a convenience/price differential compared to China.

The final reason for the cheap costs of goods (separate from delivery/returns) is China’s strong manufacturing capacity throughput, which, given the country’s current sluggish economy, has turned into overcapacity (which I wrote about in my last post), driving prices below their natural levels.

Across these three broad layers of “convenience” I observed, there are significant structural barriers to bringing these capabilities to the West. So what can Western companies borrow from their Chinese counterparts?

Chinese consumer companies — blueprint for Western success?

Rethinking consumer UI, starting with user generated discovery

One of the areas that China has out-innovated the West is in consumer UI/UX, especially as the world adopts more generative AI capabilities, and across more modalities beyond text (e.g. audio, image, video, etc.). Just as concepts like ephemerality and video as a new modality have allowed apps like Snapchat and TikTok to steal market share from other social media giants, new user experiences/application flows and new modes of interaction will give challenger apps the chance to win consumer market share in the future.

We’ll use two examples here:

TikTok, where it breaks free from the 2010s design language that many Chinese apps have, and introduces a novel UI + video as a primary modality

Little Red Book/小红书, which, while looking a bit dated on the design side of things, uses what I call “user generated content inversion” to help with discovery

Starting with TikTok, the most “obvious” innovation is its more natural vertical scroll (vs. the horizontal “tap” in Instagram stories), which further reduces user friction & increases app stickiness. Apps like Instagram Reels and YouTube shorts have since adopted this (whether these addicting apps can be considered digital opium is a debate for another day).

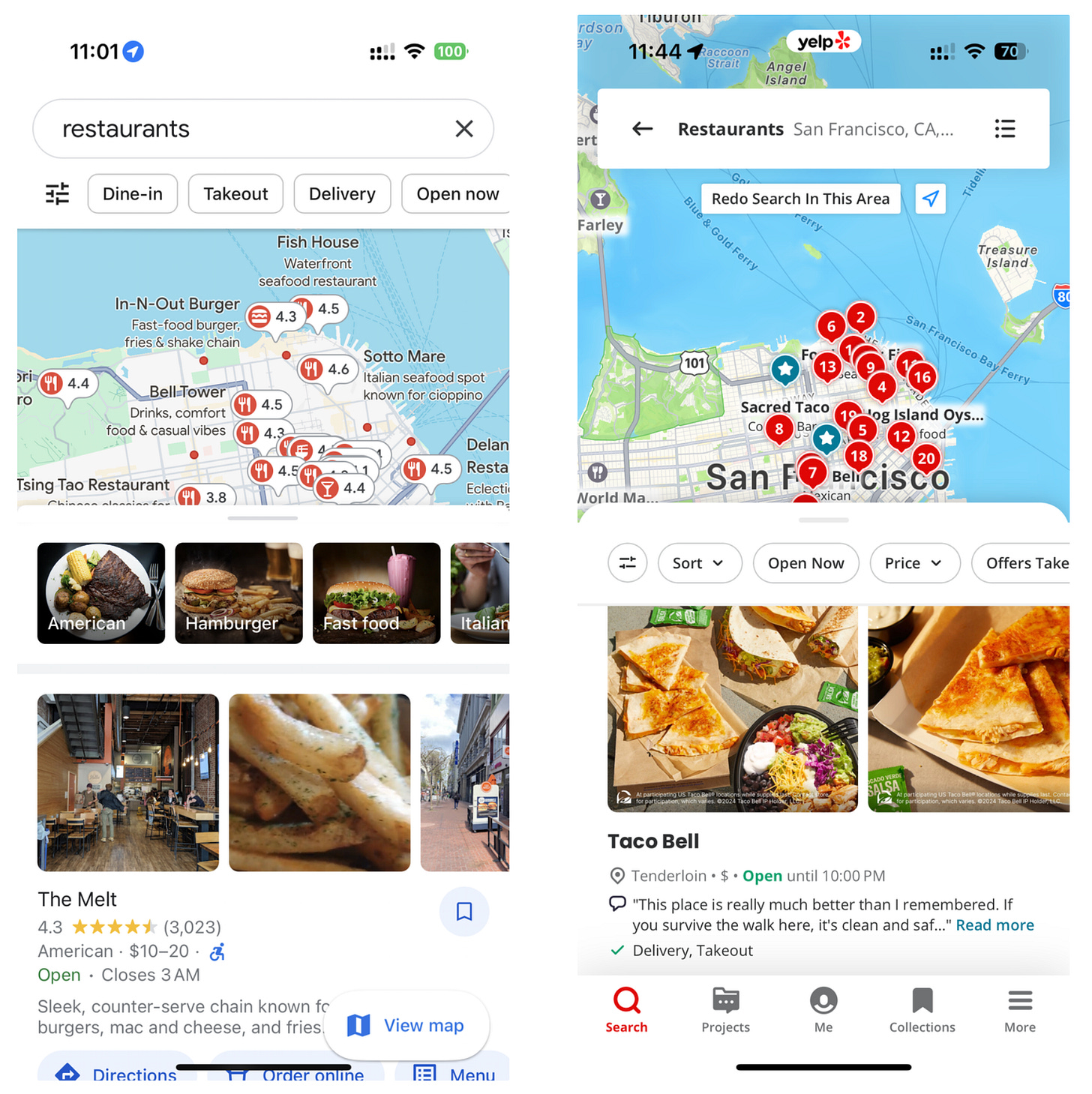

The more impressive learning for me for me, however, was how sophisticated apps like 小红书 (Little Red Book) were for discovery (new restaurants or things to do in a given city). In the US, my workflow for discovering new restaurants might be something like going to Eater (and similar websites) to discover new restaurants, then using Yelp/Google Maps for user reviews. In apps like Google Maps/Yelp, everything is maps & lists based. The issue here is that the map doesn’t REALLY give us a lot of new information. Sure, it tells us the rough location of where the restaurants are, but so does the distance feature in Google Maps! The more important insight here is that to get to the user generated content, we have to click on the restaurant first.

In the 小红书 app, the content discovery process is inverted! This means that if I’m searching for restaurants in San Francisco, a user-created post is displayed first, and I then click into it to discover interesting restaurants. The workflow here is I would read several of these posts to triangulate specific restaurants that I should go to. 小红书 now has essentially become one of the de facto apps for user discovery (it’s worth noting, however, that 大众点评/DianPing offers a more traditional “Yelp” experience)

This applies to the travel use case as well. In the US, researching “things to do” when exploring a new location would entail Googling and going through various website lists (e.g. Tripadvisor, Time Out, etc.). If a user is tech savvy, they might use something like ChatGPT/Claude/Meta’s Llama 3, which has sucked up the information from the aforementioned websites to give users one shot results.

More “savvy” users might use Google’s “site:reddit.com” feature to narrow down to truly user generated content via selecting only Reddit results, which feels like a poor imitation of the 小红书 experience.

Again, we are taken back to links and lists. With widespread access to LLMs, the future of “discovery” will be one-shot answers from our search engines. The problem is that for these queries, a lot of the underlying training data to these models are drawn from SEO-optimized websites. As the web becomes more SEO-optimized/machine generated, what will likely happen is that there will be less underlying “human” data in our models’ training data distribution. This would make it that much harder to discover that local hidden gem because that’s an answer that simply won’t come up in 1-shot LLM question-and-answering sessions. I’ve written about this in the context of programming in my Peak Data post, but as I think about how LLMs will be integrated into our lives more, this will apply to all aspects of our search experience.

At least in the short to medium term, an app like 小红书 won’t have this problem, given that user-generated content is front and center, and from the posts that I’ve seen, there is a blend of the “top” restaurants, as well as our hidden gems. The actual AI, in this case, is “relegated” to search and recommendation. In the longer term, for apps like 小红书, I see some very interesting product directions and monetization strategies—小红书 could choose to train/fine-tune LLMs on their own user data, or go down the Reddit model and open up its training data for foundation model vendors, which can be sold to Chinese large language model companies like Moonshot AI, Baichuan AI, and 01.ai.

In the West, we do have a similar app in Bytedance’s Lemon8 app, which is very much a carbon copy of 小红书. Lemon8 hasn’t quite taken off yet, given Bytedance hasn’t done an extremely aggressive (and expensive) marketing push to acquire users. As of November 2023, Lemon8 only had 2.6M aggregate downloads in the US (and in May 2024, the app had ~1M downloads globally, according to Appfigures). TikTok also enables some of these discovery use cases (albeit in a video format). If the TikTok ban goes into effect, however, it’s unclear if Lemon8 would also eventually be shut down.

As we can see, TikTok’s use of the vertical scroll + video and 小红书’s content inversion have enabled both apps to gain market share in a brutal consumer market. The more important/meta point here is that new combinations of user interface and data modalities give startups a chance to dislodge existing incumbents, who already own distribution with their hundreds of millions/billions of users. With the adoption of generative AI, I do see an opening for new, well-capitalized and extremely execution-focused startups to win. I see companies like Humane and Rabbit (both products have flopped) as very much the first generation of startups trying to reimagine how consumers interact with technology, and I’m excited to see the subsequent iterations of products in this category. For sure, consumers in the West are already overwhelmed with their existing, largely single purpose apps, but for new entrants that can overcome this user inertia will find that they can capture extremely large markets.

Single-use consumer robotics as a wedge to multi-task robots

Another success story is that of China’s various consumer robotics companies. While in the US, the tech news cycle is more dominated by high-end, general-purpose robots like Figure, Tesla’s Optimus, and 1X, which are currently more targeted towards industrial settings, China has been very focused on commercializing the near-term opportunity — task specific consumer robots (though not necessarily at the expense of developing industrial robotics). Here, the learning from Chinese companies is that a maniacal focus on commercialization is a better approach than going on scientific research adventures in capital intensive industries. The home cleaning robotics market is one example where companies like Roborock and Dreame have dominated the Western market using a commercialization-first approach.

In contrast to most cash-burning robotics companies in the West, Roborock is actually generating revenue! Like a “normal” startup, Roborock has raised ~$250M (from consumer electronics giant Xiaomi). The key difference here is that it has real products on the market and is generating significant revenues, to the tune of ~$1.22B in 2023. This is in stark contrast to many Western robotics startups, many of which are going directly for general purpose robotics. These Western startups will need to solve some fundamental scientific questions before they even get a chance to do all the practical startup things (product engineering, GTM, building out supply chains, etc.). This reminds me a bit of Russ Hanneman in the hit show Silicon Valley when he tells Richard Hendricks that it’s better to be “pre-revenue.” What Russ means is that it’s almost better to raise venture dollars on a story, especially if that story is we’ll replace all your workers in all industrial settings, vs. generating revenue so that “finance people” can actually price the company. I disagree with this approach and believe that a lot of these general purpose robotics companies will get smoked by robotics companies that are actually focused on bringing products to market.

Roborock, in contrast, is building products with technology that is ready now, and pricing products competitively. Meanwhile, the company is concurrently mastering all the other hard things in a startup, from building out distribution to making its supply chains efficient to actually building a complex product. Even this is not “easy,” and requires the integration of various technologies/engineering concepts like control systems, SLAM, and computer vision. The benefit for Roborock is that when the next generation of robotic technologies is ready for mass market adoption, it will already have the brand recognition, distribution, and supply chain in place.

As an aside, what’s also interesting is how companies like Roborock are pricing their products. Similar to how Chinese EV makers price their cars lower than the equivalent vehicles in Europe (given how competitive things are in China, as I wrote about in my last post), a similar dynamic exists for the home robotics market. The Roborock S8 Pro Ultra, the most high-end cleaning robot that the company offers in the US, retails for $1400 (~¥10,100) on Amazon. The G20, a newer, even more advanced model, only retails for ¥5200. This means an older-generation Roborock is almost 2x as expensive in the US! Chinese robotics companies are actually juicing their margins as a result of entering the Western markets, which runs counter to the common sentiment that Chinese companies always undercut Western companies on price to steal market share.

So how should Western companies capitalize the consumer robotics opportunity?

Mapping the “job to be done” to market-ready technologies

The Western market has two interesting characteristics that are different than that of China’s:

The cost of human labor is significantly more expensive in the West, so there are categories of work that make economic sense to be automated in the West, but not in China, due to this cost differential

Some types of work are different — stemming from where people live in US and Canada (more single family homes), so there are tasks like roof/gutter cleaning that don’t exist in China, where most people live in condos

With these two market characteristics in mind, the framework I like to use to understand the opportunity is mapping the job to be done to technologies that are already market-ready. Looking at the chart below (courtesy of Digital Native), we have tasks ranging from landscaping to roofing. An industrious entrepreneur might then choose to map out the tasks that each “contractor” does as well as other household tasks that aren’t fully automated yet, like cooking. This would be the “search space” of all potential robotics ideas.

The next step is mapping these tasks to off-the-shelf technologies in order to develop immediately commercializable products. As these companies reach positive unit economics, they can funnel excess profits into bringing existing research that is almost market-ready to tackle other “jobs to be done” (some interesting research includes Google’s PaLM-E, Stanford’s STAIR, and Berkeley’s collaboration with Agility Robotics).

Given the number of these contractors across the different service types in the chart, there are many “jobs to be done” that could potentially be automated. Now, the distinguishing factor for some of these tasks is that they might be extremely expensive, but lower frequency (something like roof cleaning), so it might not make sense for a single household to buy a robot for each task. This means that new categories of businesses leveraging robotics might need to innovate on the business model side of things as well.

From a venture perspective, in an era where the cost of software development is trending down due to AI and automation, the world of “atoms” is where the venture dollars from large funds can actually be effectively deployed. Kyle Vogt’s “Bot Company” might be one of the earlier entrants here, having recently raised $150M for its robotics startup, but I think it’s the first of many.

Consumer Startups are Dead, Long Live Consumer Startups!

The common sentiment is that consumer investing is dead, with multiple venture firms retreating from the category altogether or cutting investors on their consumer teams. However, being contrarian (and right), however, is where the returns lie.

This is not to say everyone should build consumer startups — the laws of gravity in consumerland still apply (relatively binary outcomes in consumer social, high CAC, etc.). But Chinese companies have shown us there are avenues of exploration that haven’t been fully exploited in the West yet, and these avenues may be sources of alpha for the next generation of consumer entrepreneurs, and the investors backing them.

Huge thanks to L. Shen, Will Lee, John Wu, Danielle Jing, and Andrew Tan for the feedback on this article.