Parallel Tracks: observations from the Jade Empire (Part 1)

I recently visited China for the first time in four years (since pre-COVID). Outside of the customary overeating, which at times felt like my food baby had its own food baby, I had the opportunity to observe some interesting technology and economic trends. These trends were especially fascinating in the context of the current Great Power Conflict between the US and China. In this post, I contend that China and the US are running “parallel” technology races with different win conditions, with China aiming to reach independence on certain strategic high-end capabilities, while the US is in a race to onshore domestic world of atoms (physical things) capabilities and containing China’s technological rise.

I first give an on-the-ground overview of China’s current economic environment, which should serve as a helpful primer on why China desperately needs to catalyze its economy and achieve its strategic priorities before it’s too late. I then analyze China’s technology “stack” in comparison to those of the US in the context of reaching strategic technological independence. To explore this stack, I use a modified version of the US Air Force’s “high-low” framework (in which the Air Force would procure a smaller number of high-end aircraft, complemented by a much larger contingent of cheaper/less-capable aircraft, e.g. F-15s vs. F-16s or F-22s vs. F-35s).

With this high-low framing, China has largely surpassed the Western world on the low-end, particularly in technologies that are consumer facing. Here, the delta (in terms of capabilities and cost) in consumer products presents an an attractive opening for entrepreneurs in the West. On the high end, while the West still leads in many categories, China has started to match, and in some cases, surpass Western capabilities (especially in the world of atoms).

Note: I define the “low-end” and “high-end” as the following:

Low-end: commodity software and hardware that reasonably capable teams infused with capital can quickly bring to the market. Does not readily contribute to the strategic positioning of rival nations

High-end: software systems that require a significant knowledge or compute hurdle to build, as well as hardware in which the bar for manufacturing know-how, required manufacturing precision, and capital intensity is extreme. These capabilities are considered the strategic priorities for the leaders of present-day great powers

For Part I of this post, I focus on the “high-end”, given it’s the part of the stack that is seeing the most competition. Part II of the post, meanwhile, will focus on my observations on the “low-end” stack. Let’s dive in!

China and the era of the great slowdown

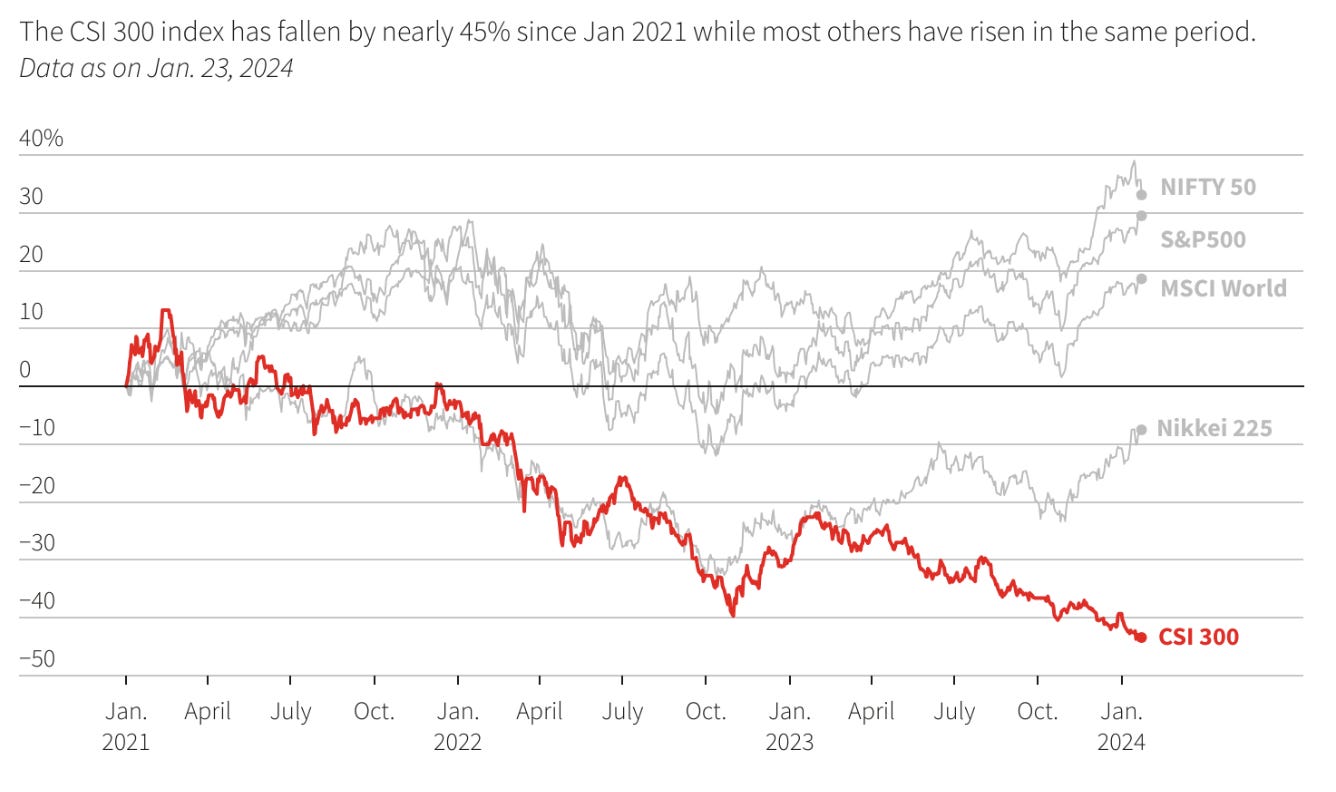

The most apt word to describe the current Chinese economy is sluggish. Starting with public equities, the CSI 300 index has been battered (despite the recent “artificial” rally driven by an estimated $57B deployed to stabilize China’s capital markets). There has also been a collapse in FDI (foreign direct investment) into China, which only totaled $33B in 2023, and more than a 90% drop from 2021 highs. And given tight capital controls, there is strong demand for Chinese funds tracking foreign markets, with many of these funds trading significantly above NAV (net asset value) of the underlying securities.

Second, due to a variety of factors (e.g. import tariffs levied by the US on Chinese exports, overproduction capacity, compressed wages, etc.), China is also experiencing deflation in a world where many other countries are still grappling with inflation. This time, however, it is unclear whether China can export its way out of deflation.

The triple whammy here is collapsing real estate prices. The dynamic in China is that without many other viable investment asset classes, residential real estate has become the main vehicle for investment and speculation. It’s estimated that 70% of the average Chinese citizen’s net worth is tied up in real estate. While official figures for price declines aren’t terrible, the situation on the ground is that many closed transactions have seen more than 20% price reductions vs. 2022 highs. Anecdotally, I’ve seen even steeper declines in some cases given the large bid-ask spread.

With public equities AND real estate prices in free fall, consumers are rightly wary of depleting their cash reserves despite China’s current deflationary environment. This was probably the first time since living in/visiting China (between 2005-2020) that I could almost “feel” the downturn. These are all indications that China is running out of time to transition into a full fledged advanced economy before they fall into the infamous middle-income trap (not even accounting for western economic and technology pressures).

These “macro trends” are quite visible on the ground. The malls in China are more empty than prior years (many of the “top” places in China still see a lot of foot traffic, however). In Chengdu, for example, at the 新世纪环球中心/New Century Global Center (largest building in the world in terms of floor area), the bulk of the mall sits empty. While Chengdu is not a true 一线城市/tier-one city, it still houses a population of over 21 million!

Restaurants, even high end ones, are consistently offering 套餐/set menus to entice diners. The interesting thing here is that these are typically group set menus where you would pay ahead of time (say for a party of 4), and then choose from a selection of dishes. Durable goods, meanwhile, have also deflated quite a bit, and domestic giants like Pinduoduo and ByteDance are locked in brutal price wars.

With China’s current economic backdrop in mind, it’s understandable that China needs to do something to get out of its economic funk. Given the relative maturation of technologies at the low-end, as I will expand upon in the next section, and for strategic reasons, China is trying to win on the high-end.

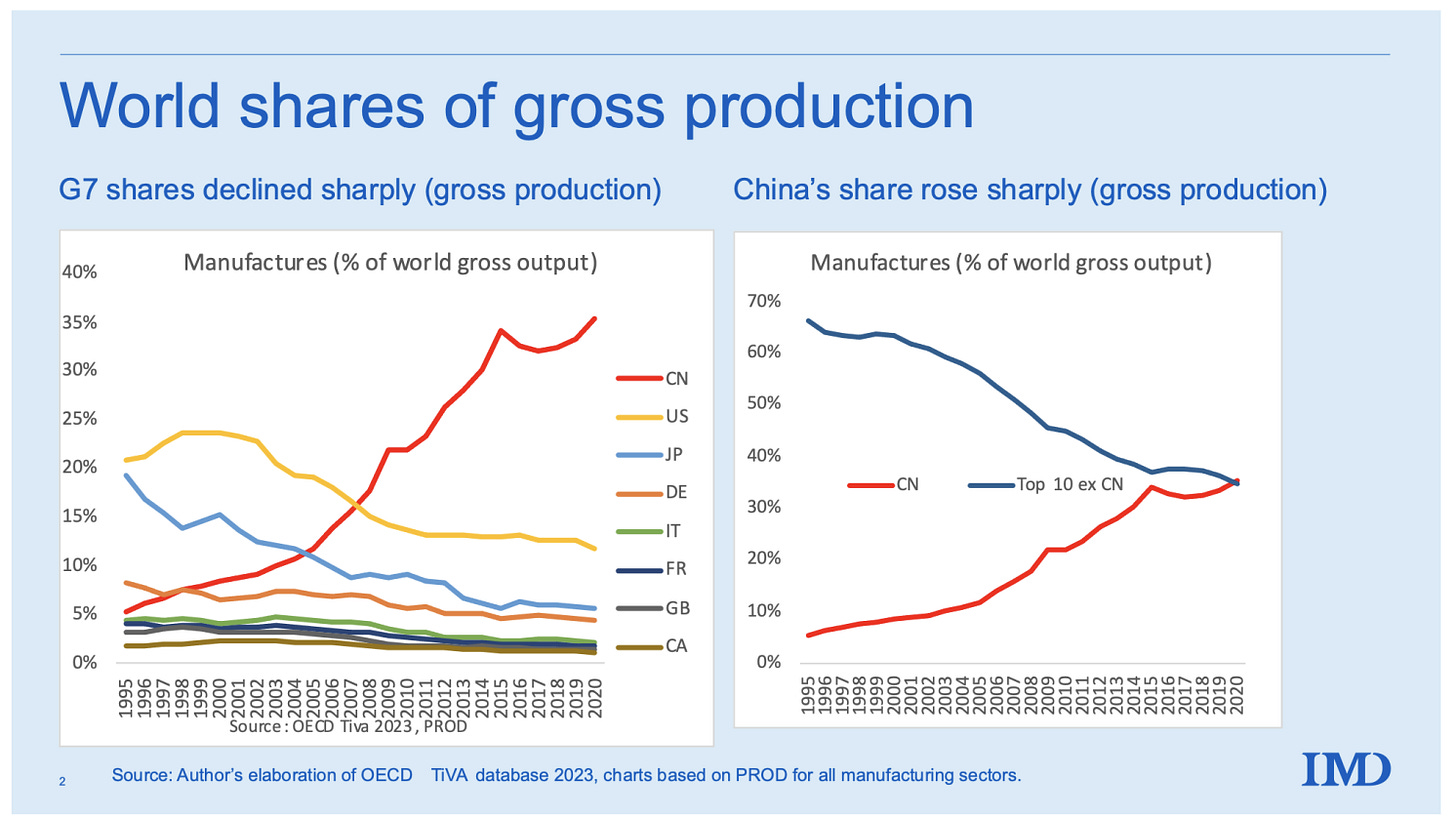

China has broadly eclipsed the West on the low-end part of the technology stack

To understand why the low-end part of the stack doesn’t matter in this parallel technology race, it’s helpful to look back in history. In contrast to the US, which emerged as a major superpower at the end of World War II, China has only had the past few decades since the Open Door Policy to develop its own economy. As with many developing countries, China started its growth as an low-cost manufacturing hub. To facilitate this, China embarked on massive infrastructure buildouts (roads and bridges, in American political speak) and attracted significant foreign investment dollars (especially joint ventures where IP transfers needed to take place). Over the next decades, China became the undisputed global manufacturing powerhouse.

As it continued to grow, China was able to layer on more industries, especially in areas like information technology, giving birth to companies like Alibaba, Baidu, and Tencent, JD, and Huawei (and more recently upstarts like ByteDance and Pinduoduo). The initial iterations of these companies were decidedly “low-end” in that they played mostly in the world of bits (software). These new industries served as additional drivers of China’s economic growth in the past two decades (and a reason why Chinese venture funds performed so well!). What this means is that, at least on the consumer side of things, the “average” citizen in a large Chinese city is able to experience a level of convenience that is currently unmatched in the West. I plan on doing a deep dive on this in Part II of this post, but the main point here is that this convenience is achieved using a combination of a robust super app ecosystem, extensive last mile delivery/transportation, cheap labor costs, and use of “low end” commodity technology (e.g. consumer robotics, computer vision, etc.). My co-founder Will and I are quite bullish that some of these capabilities can be imported/replicated here in the West.

While this growth has been impressive, China understood even as early as 2007 (in a statement by former Premier Wen Jiabao) that eventually, it would need to shift from an investment/export driven economy to one that was predominantly driven by domestic consumption.

Fast forward to recent years, that statement was remarkably prescient. China faces significant headwinds, ranging from manufacturing overcapacity to weak domestic demand (Chinese wage growth can’t support the required domestic consumption) to punishing tariffs and technology sanctions. This time, however, China can’t rely on infrastructure buildouts (it already has ample infrastructure) to energize economic growth.

Nor can China rely on the “low-end” layers of the technology industry that has enabled so much of the consumer convenience in China (e.g. Alipay/WeChat pay, e-bike fleets, fast delivery). More importantly, in the context of China and US parallel races, apps like TikTok/Shein/Pinduoduo, despite the limelight they receive in the American politic news cycle, doesn’t really move the needle in helping China gain technology sovereignty. It is the chips that these apps and AI models run on, and more broadly the ability to manufacture high-precision, world of atoms things, that actually matter. It is therefore on the “high end” that the battle lines of this global power conflict are drawn.

On the high end, China is catching up, especially in the world of atoms

The high end spectrum of technologies is where things get interesting, and where China’s dominance in EV serves as a proxy for its ability to very quickly bring a world of atoms product to market (design, manufacturing, integration). I cover three layers of technology, from AI capabilities, to semiconductor design & fabrication, to EVs. Here, China’s manufacturing institutional muscle will be critical as the technology uncoupling between China and the West increases.

US currently holds a tenuous lead on AI model development

Starting with the top of the stack (the furthest away from the world of atoms), in AI, its clear that that the US has the lead, with multiple companies and industry research labs moving from strength to strength. OpenAI’s GPT-4 and Anthropic’s Claude 3 ensures that the US is still on top of the mountain. Google, despite its recent controversy, is still innovating at the model architecture level with its 10 million token context window for its Gemini 1.5 Pro model. There’s also a lot of progress on the non-LLM side of things (see OpenAI’s Sora text-to-video model).

In terms of open-source, Meta is committed pushing the boundary with its upcoming Llama 3 class of models, and has committed an estimated $9B of compute budget on H100s alone (actual figures are likely lower due to volume discounts). Behind these giants, we have companies like Adept and Cohere (RIP Inflection) in the US (and European upstarts like Mistral and Aleph Alpha. Mistral is VERY strong here). The Europeans do have a penchant for self-harm, however. The net net here is that enterprises and consumers in the West have a lot of models to use and fine-tune.

So how does China stack up?

Source (LMSYS Chatbot Arena Leaderboard as of March 28th)

In terms of model capabilities, China has demonstrated that it’s also able to train quite competitive models (see Qwen 1.5-72B-Chat which ranks 9th, and Yi-34B-Chat, not pictured, but ranks 20th, both accurate as of March 28 2024), though they are a step behind the leading edge. Looking at the performance of leading open models (e.g. Databricks’ DBRX, which China can also use) relative to closed source models from OpenAI/Anthropic, the West is ahead by 2-3 years at best, and potentially less in areas like multi-modal models. Now, the way I think about model building capabilities are the four pillars consisting of model architecture, large-scale systems know-how, data, and available compute.

Breaking these down:

Links (here, here, here, and here)

Given China’s powerful models, it’s obvious that US sanctions are far from perfect. China can simply buy cloud compute from third-party nations, and there is evidence that Chinese companies can still source high-end GPUs and have also been modifying gaming GPUs like the RTX 4090 (this indirection does add to China’s training and inference costs, however).

The other way to look at this is AI adoption. As mentioned previously, western enterprises have a large number of vendors to select from for their business cases, and consumers have things like ChatGPT/Claude/Le Chat (or if they are enthusiasts, can use something like LM Studio or Ollama to run powerful models locally). In China, getting access to ChatGPT requires a VPN (which a lot of white collar workers have), an annoying additional step. In the longer term, I wondering if a) access to weaker models or b) state-sanctioned “nerfed” models will prove to be a drag on productivity for white collar work.

The US has yet to achieve its own fabrication sovereignty on the leading edge

At the software layer, we can see that given the relative lack of defensibility of model architectures/access to data, access to compute is where the US is the logical (and only) place for the US to apply pressure. To properly do that, the US needs to first ensure fabrication independence from Taiwan. I had first written about this last year, when I argued that replicating TSMC’s fabrication capabilities onshore is extremely crucial (and the US is trying via the CHIPS Act).

Now, while the first dollars from the CHIPS Act are starting to be deployed, we’re already seeing why the world of atoms is so hard. TSMC’s $40B factories in Arizona will already be a step behind the leading edge by the time they come online (N4 in 2024/2025, N3 in 2026, with possible delays). The US essentially needs multiple CHIPS Acts to continue to incentivize TSMC’s leading-edge fab investments stateside. Therefore, in any potential “hot war”, the US will also lose access to its most advanced chips. The dark horse here is Intel, and whether the legendary Pat Gelsinger can push the company to once again regain process leadership and reclaim what has for decades been an American birthright.

Source. Taiwan will already be on the N2P/N2X/N3A process by 2026

China demonstrates competence in chip design

China, meanwhile, is taking a “whole nation” approach to strategically critical areas (which includes semiconductor design and fabrication). Here, China is demonstrating remarkable resilience despite crippling sanctions ranging from end-products like Nvidia and AMD’s graphics accelerators to ASML’s lithography systems. In Q4 of last year, Huawei unveiled the Kirin 9000S SOC (system on chip) running on the 7nm process, which surprisingly performed well compared to Snapdragon chips running on a newer 5nm process. On the AI accelerator side of things, Huawei is expected to put out a reasonably competitive product via its Ascend 910B accelerators that performs at a similar level to Nvidia’s A100 (which despite being launched in 2020, is still an extremely popular GPU for AI workloads). As a side note, Nvidia is very much ahead with the current-day champion, the H100, and its upcoming Blackwell chips.

Source. Geekbench results for the Kirin 9000S, followed by US-based Qualcomm Snapdragon offerings, and finally the 天玑/MediaTek 8100

China is still quite behind on fabrication

At this point, China has become quite competent at chip design. Fabrication is another matter. Due to import restrictions on EUV (extreme ultraviolet) lithography machines from ASML (required to create leading edge chips), China only has access to older DUV (deep ultraviolet) machines, and there are even some restrictions on these! As a result, China’s national champion SMIC needs to aggressively use multi-patterning to get to 7nm/5nm, and has been rumored to only achieve quite uneconomical ~50% yields, vs. an industry standard of 90% yields. The key question here is whether China can replicate an entire semiconductor fabrication stack in-house, or find workarounds to catch up to the West (which will be on the 2nm process soon). Another risk is here is that the next level of sanctions could result in ASML withholding support engineers and spare parts, forcing China to draw down its existing stockpiles.

The US has clearly fallen behind in EV manufacturing & adoption

Switching gears (pun intended) to electric vehicles, the US (and the rest of the western world) is clearly falling behind. Companies like Ford, GM, Mercedes and Volkswagen have already scaled back or delayed their plans to roll out EV-only fleets. Here, we see a clear example where the US ability to iterate on the design and manufacturing of hardware have slipped significantly. In North America, Tesla is essentially the only “scaled” US-based EV manufacturer, and the only vehicle one can readily purchase. In recent months, when I was in the market for an EV in Canada, two of the brands I was interested outside of Tesla (BMW i5 and Hyundai’s IONIQ 5/6) in had multi-month waits, and these cars are expensive!

Starting from top left and ending in bottom right: BYD, NIO, IM Motors (JV between SAIC, Alibaba, and Zhejiang Hi-tech), Zeekr (Geely)

Conversely, in China, competition between local manufacturers is fierce, and Chinese vehicles come with significantly more features and at lower cost relative to the West. Just this week, Xiaomi threw its had in the ring with its SU7 vehicle which costs $4K less than a Model 3! I’ve test driven around 10 different vehicles at this point in the 150K-300K RMB price point (~$21-42K USD), and these vehicles are quite capable. Many “premium” features come in standard—long range (500-800km/~300-500 miles), snappy infotainment systems, quality of life features (360-degree cameras, parking assist, built-in voice assistants, etc.). The breadth of technology packed into these vehicles means that China was also able to develop crucial technologies upstream. For example, China now has a strong LIDAR industry led by companies like Hesai.

In terms of driving dynamics, the cars in general handle quite well in normal urban/suburban scenarios. Cars on the lower end of the price spectrum (think $20k and under) might exhibit some tire spin when doing a 0-100 km/h (~0-60mph) acceleration test, but something like a BYD 汉/Han (which is a sedan around ~$25k USD) is extremely planted on the road and its straight-line acceleration to 100 km/h is only 3.9 seconds! In normal driving (steering, highway overtake, driver ergonomics), China is at least a generation ahead of the western EV efforts outside of Tesla (and Tesla itself is quite “basic” in terms of its interior amenities/sophistication and isn’t very competitive in China anymore). To get something truly good, you’d need to step up to a Porsche EV. Now, it may be that for conditions at the boundary, a Porsche EV might perform better, but the average EV shopper isn’t trying to set lap records at the Nurbergring (or spend $100K)!

The other point I want to make is that the accusations that Chinese manufacturers are flooding the market with cheap vehicles is pretty laughable. Different Chinese manufacturers are locked in vicious price competitions. These manufacturers are actually pricing the same vehicles much higher in the west! Looking at the Nio ES6 (called EL6 in Europe), the base model of the car starts at €75k/~$81k in Europe, and is only ¥338K/$47k (March 31st 2024 pricing) in China! If anything, Chinese EV manufacturers are generating additional profits in western markets to offset the much lower margins of the vehicles sold in China. The US administration’s actions to limit Chinese EVs by labeling these cars as a security threat therefore seems to be more to be geared towards getting union votes than anything else. The net result of this, however, is that American consumers are getting fleeced with the limited options they have. And it’s doubtful that the Detroit “Big Three” will be at all competitive in the global export markets.

Why does the “high-end” matter more now than ever?

China‘s EV ascendancy is so interesting for me (outside of my 15 year obsession with cars that began with the Lancer Evolution/Subaru WRX STI) because it proves that real, durable advantage for nation states lie in things closer to the world of atoms.

The ability to “outproduce” rivals has been one of the reasons that the US has historically come ahead in prior Great Power Conflicts. Now, I have no doubt that wartime US has the will to ramp production quickly. The issue with technology now is that things are more complex compared to the past (from a development, supply chain interdependence, and production perspective). Going back to our EV analysis, Apple recently made a strategic retreat from building their own vehicles. Doing some back of the envelope math here, Apple’s car project had ~2,000 employees, which at a very conservative ~$300k per fully-loaded employee, would cost $600M/year. Over the span of 10 years (and including costs like hardware and facilities), this means Apple spent at least $10B on R&D for a product that never made it to market. Now, it’s important to note that Apple obviously has a reputation for perfection that a company like BYD doesn’t need to match, but does highlight how hard this stuff is!

Or, looking at semiconductors, going from announcing a fab to the same fab producing usable chips is measured in years. We’ve also seen, via the conflicts in the Red Sea, that the US is using expensive missiles to defend its ships against relatively cheap Houthi drones. This is why I’ve been thinking about the concept of “front-loading” investments deep-tech, long-horizon projects a lot recently (whether it’s new product development or manufacturing throughput). The idea is that we front-load hard things so we have these capabilities on hand when we desperately need them. The open question for me now is whether US companies can rapidly bring combat systems to market to counter asymmetric threats, and whether it can produce things like the SM-3/SM-6’s quickly enough to replenish inventory in the event of conflict with near-peer adversaries (and bring new capabilities like the Collaborative Aircraft Project to life). On the innovation side, we’re at least seeing an interest in American Dynamism, and the investment dollars that will surely flow to new defense startups (Anduril is probably the most notable company that’s attempting to become the next defense prime). Given the current state of the world, it feels like the production shortfall will be especially exacerbated in the off chance that the US needs to deploy resources, attention, and lethality across three theaters of operation (Europe, the Middle East, and Asia).

So how should the US and China think about their respective technology “win” conditions in this parallel race?

For China, it’ll be whether it can:

Achieve technology independence in core areas like semiconductor fabrication

Be the manufacturing hub for the rest of the world (outside of North America and Europe) to overcome western sanctions and tariffs, and successfully competing/winning against western offerings in those geographies

Continue to circumvent Western import tariffs & technology sanctions (see the correlation between China’s exports to Vietnam, and Vietnam’s exports to the US)

For the US, it’ll be whether it can:

Onshore/friendshore semiconductor fabrication

Control of or heavy influence over supply chain, largely maintained by western allies

Improve the cost efficiency for new technological innovations to maintain technological hegemony

Increase manufacturing throughput for combat systems

Minimizing any “unforced errors”. I didn’t go into this as deeply here, but things like the White House AI Executive Order, the European AI Act, and the recent EU investigation into Mistral for its Microsoft partnership could actually slow down progress areas where the West actually has a lead

For both the US and China, we’re already seeing the rippling effects of this “race” via policy and rhetoric, and the exciting (and a little scary!) thing is we’ll probably see the outcome of the race before the decade is out.

Huge thanks to Will Lee, John Wu, Maged Ahmed, Andrew Tan, and as well as various industry experts for helping review this post! If you’re interested in chatting tech & policy, please don’t hesitate to get in touch! I’m around on LinkedIn and Twitter!

P.S. Jade Empire was one of my favorite games growing up, so this post is also a plea for the folks at Bioware to make a sequel.